- When and how it became a method of learning?

- HISTORY OF ACCOUNTING

(References taken from books and www.wikipedia.com)

Token accounting in ancient Mesopotamia

Map of the Middle East showing the Fertile Cresent circa. 3rd millennium BC

The earliest accounting records were found amongst the ruins of ancient Babylon, Assyria and Sumeria, which date back more than 7,000 years. The people of that time relied on primitive accounting methods to record the growth of crops and herds. Because there is a natural season to farming and herding, it is easy to count and determine if a surplus had been gained after the crops had been harvested or the young animals weaned

During the period 8000–3700 BCE, the Fertile Crescent witnessed the spread of small settlements supported by agricultural surplus. Tokens, shaped into simple geometric forms such as cones or spheres, were used for stewardship purposes in relation to identifying and securing this surplus, and are examples of accounts that referred to lists of personal property. Some of them bore markings in the form of incised lines and impressed dots. Neolithic community leaders collected the surplus at regular intervals in the form of a share of the farmers’ flocks and harvests. In turn, the accumulated communal goods were redistributed to those who could not support themselves, but the greatest part was earmarked for the performance of religious rituals and festivals. In 7000 BCE, there were only some 10 token shapes because the system exclusively recorded agricultural goods, each representing one of the farm products levied at the time, such as grain, oil and domesticated animals.The number of token shapes increased to about 350 around 3500 BCE, when urban workshops started contributing to the redistribution economy. Some of the new tokens stood for raw materials such as wool and metal and others for finished products among which textiles, garments, jewelry, bread, beer and honey.

The invention of a form of bookkeeping using clay tokens represented a huge cognitive leap for mankind.[11] The cognitive significance of the token system was to foster the manipulation of data. Compared to oral information passed on from one individual to the other, tokens were extra-somatic, that is outside the human mind. As a result, the Neolithic accountants were no longer the passive recipients of someone else’s knowledge, but they took an active part in encoding and decoding data. The token system substituted miniature counters for the real goods, which eliminated their bulk and weight and allowed dealing with them in abstraction by patterning, the presentation of data in particular configurations. As a result, heavy baskets of grains and animals difficult to control could be easily counted and recounted. The accountants could add, subtract, multiply and divide by manually moving and removing counters

The Mesopotamian civilization emerged during the period 3700–2900 BCE amid the development of technological innovations such as the plough, sailing boats and copper metal working. Clay tablets with pictographic characters appeared in this period to record commercial transactions performed by the temples. Clay receptacles known as bullae, were used in Elamite city of Susa which contained tokens. These receptacles were spherical in shape and acted as envelopes, on which the seal of the individuals taking part in a transaction were engraved. The symbols of the tokens they contained were represented graphically on their surface, and the recipient of the goods could check whether they matched with the amount and characteristics expressed on the bulla once they had received and inspected them. The fact that the content of bulla was marked on its surface produced a simple way of checking without destroying the receptacle, which constituted in itself an exercise in writing that, despite being born spontaneously as a support for the existing system for controlling merchant goods, ultimately became the definitive practice for non-oral communication. Eventually, bullae were replaced by clay tablets, which used symbols to represent the tokens.

During the Sumerian period, token envelop accounting was replaced by flat clay tablets impressed by tokens that merely transferred symbols. Such documents were kept by scribes, who were carefully trained to acquire the necessary literary and arithmetic skills and were held responsible for documenting financial transactions. Such records preceded the earliest found examples of cuneiform writing in the form of abstract signs incised in clay tablets, which were written in Sumerian by 2900 BCE in Jemdet Nasr. Therefore “token envelop accounting” not only preceded the written word but constituted the major impetus in the creation of writing and abstract

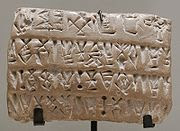

Complex accounting tokens made

of clay, from Susa ,Uruk Period,

cira 3500 BCE. Department of Oriental

Antiquities, Louvre.

Some Of the Old Ancient Writings Relating To Ancient Accounting Techniques

Ancient Accounting Tablet Susa Louvre

Ancient Accounting Tablet Susa Louvre Ancient Accounting Clay Envelope Susa Louvre

Ancient Accounting Clay Envelope Susa LouvreAccounting in the Roman Empire

The Roman historians Suetonius and Cassius Dio record that in 23 BC, Augustus prepared a rationarium (account) which listed public revenues, the amounts of cash in the aerarium (treasury), in the provincial fisci (tax officials) , and in the hands of the publicani (public contractors); and that it included the names of the freedmen and slaves from whom a detailed account could be obtained. The closeness of this information to the executive authority of the emperor is attested by Tacitus' statement that it was written out by Augustus himself.

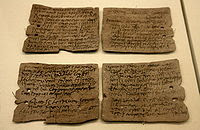

Records of cash, commodities, and transactions were kept scrupulously by military personnel of the Roman army. An account of small cash sums received over a few days at the fort of Vindolanda cira 110 CE shows that the fort could compute revenues in cash on a daily basis, perhaps from sales of surplus supplies or goods manufactured in the camp, items dispensed to slaves such as cervesa (beer) and clavi caligares (nails for boots), as well as commodities bought by individual soldiers. The basic needs of the fort were met by a mixture of direct production, purchase and requisition; in one letter, a request for money to buy 5,000 modii (measures) of braces (a cereal used in brewing) shows that the fort bought provisions for a considerable number of people.

The Heroninos Archive is name given to a huge collection of papyrus documents, mostly letters, but also including a fair number of accounts, which comes from Roman Egypt in 3rd century CE. The bulk of the documents relate to the running of a large, private estate is named after Heroninos because he was phrontistes (trans. manager) of the estate which had a complex and standarised system of accounting which was followed by all its local farm managers.[ Each administrator on each sub-division of the estate drew up his own little accounts, for day to day running of the estate, payment of the workforce, production of crops, the sale produce, the use of animals, and general expetidirure on the staff. This information was then summarized as pieces of papyrus scroll into one big yearly account for each particular sub—division of the estate. Entries were arranged by sector, with cash expenses and gains extrapolated from all the different sectors. Accounts of this kind gave the owner the opportunity to take better economic decisions because the information was purposefully selected and arranged.

hey can you write about professional accounting??

ReplyDelete